HousingPolicy.org is a resource site designed to help local policymakers understand local housing policy options and identify more resources to support affordable housing. View Website

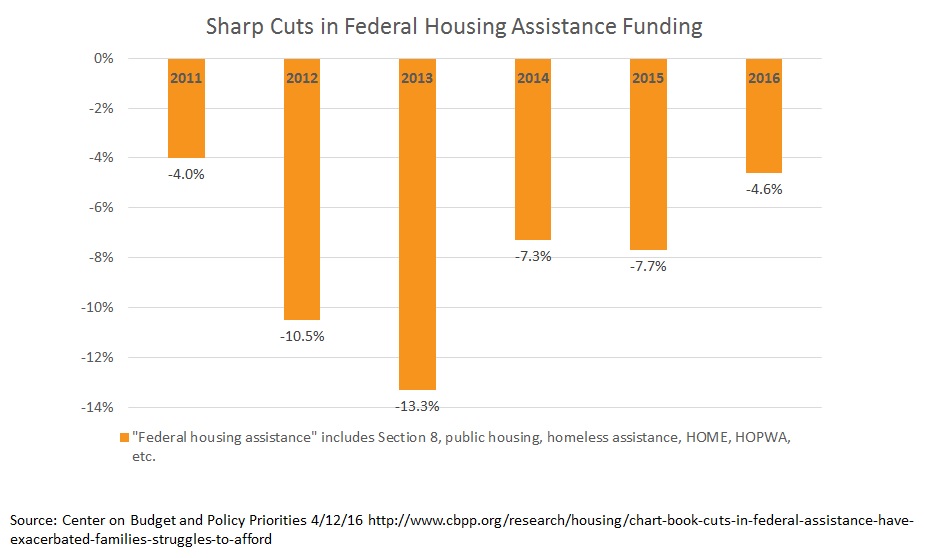

Declining Federal Housing Assistance Funds

Budget cuts have led to sharp reductions in many federal affordable housing programs, particularly programs that subsidize the production of new affordable housing properties. The Federal HOME program budget, for example, fell by 62 percent between 2005 and 2015.*

In most cities, inclusionary housing is just one tool in a suite of local policies intended to address the affordable housing challenge. A study of 13 large cities showed that nearly all of those with inclusionary programs also manage the investment of federal housing funds and issue tax-exempt bonds to finance affordable housing. Most also used local tax resources to finance a housing trust fund, and many had supported land banks and community land trusts as well. About half of those cities took advantage of tax increment financing, and a growing minority established tax abatement programs that exempt affordable housing projects from property taxes. While the exact mix of programs differed from one city to the next, every city employed multiple strategies.*

Communities that want to make a real difference in the supply of affordable housing must pursue multiple local strategies. Inclusionary housing is often implemented alongside one or more of these local strategies.

Common Questions

Probably Not: Inclusionary housing is only ever one among several tools that cities deploy to address the dire need for more affordable housing and the full set of policies is not enough to meet the full need in most cities. But that is no reason not to do all that we can. Denver City Council member Robin Kniech says “no one ever says we shouldn’t pave the roads just because we can’t fill every pothole.”

While inclusionary housing is only one tool in the toolbox, it’s an important one. Nationwide, 258 inclusionary housing programs reported creating about 110,000 affordable homes. Also, 123 programs, some of which overlap with the 258 programs reporting units, reported collecting $1.76 billion in fees to use for affordable housing.

The way you design your program can make a difference in how many units it produces. While the average production rate across all programs is 27 units per year, excluding programs that have produced zero units, average production rate for the country’s top 20 programs is 235 units per year—almost 10 times greater (Wang and Balachandran, 2021). The most productive programs share certain features: they are mandatory, offer incentives, allow developers flexibility with multiple options for compliance, and require long-term affordability.

Yes: In some cases in-lieu fees collected from developers are invested in offsite affordable housing projects that also use federal housing programs like the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program. In some communities, developers are able to apply for federal funding for onsite affordable units also. However, inclusionary programs have to offer clear guidelines to ensure that public funds are used to expand the number of affordable housing units or to serve more lower-income residents than would otherwise be served by the inclusionary units.

A few communities actively encourage developers to utilize other housing subsidies to help offset the cost of building required affordable units. This position seems to be more common in communities with a surplus of affordable housing funds. Many communities, however, face an acute need for affordable housing and high demand for scarce affordable housing subsidy funds. These cities will generally prohibit developers from ‘double counting’ units (i.e. using other affordable housing programs to subsidize units that are required by the inclusionary housing program) because these affordable housing funds are limited. To the extent that inclusionary developers are using public affordable housing funds to offset their costs, the program is not producing additional affordable housing beyond what would have been provided in any event.

Many cities adopt policies somewhere in the middle, allowing some affordable housing funds to be utilized but prohibiting others. In general, cities are more cautious about using funds that are highly limited. For example, many cities will allow developers to utilize tax abatements but prohibit the same projects from applying for housing grant funds. A second general guideline is that access to external funding should be balanced against the burdens required or requested of the developer. If cities wish to maintain their inclusionary policies, yet the inclusionary rules make development extremely difficult, they will often err on the side of allowing more external subsidies to be used.

Use of the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program can be more complicated in part because there are two different types of LIHTC. The so-called 9 percent credits provide a large share of the cost of eligible projects and as a result they are in very high demand and limited supply. The 4 percent credits provide relatively less subsidy and require relatively more investment from local sources and private debt, and as a result they are in less demand. An inclusionary project that accessed 9 percent credits might be ‘taking them away’ from another local affordable housing project while the same project could use the four percent credits without affecting other eligible local projects. For this reason there has been a trend for inclusionary housing programs to allow developers to use 4 percent but not 9 percent credits either in on-site or off-site projects.

San Francisco, California uses its tax credits to achieve deeper affordability. Generally, the city does not allow developments to use any subsidies (local, state or federal). However subsidies can be used, with written permission, to deepen the affordability of a unit beyond the level required by the program. Additionally, if 20 percent of their units are affordable to people making 50 percent of AMI, the four percent tax credit can be used. The percentage increases to 25 percent for off-site production.

♪-1200x300.jpg)