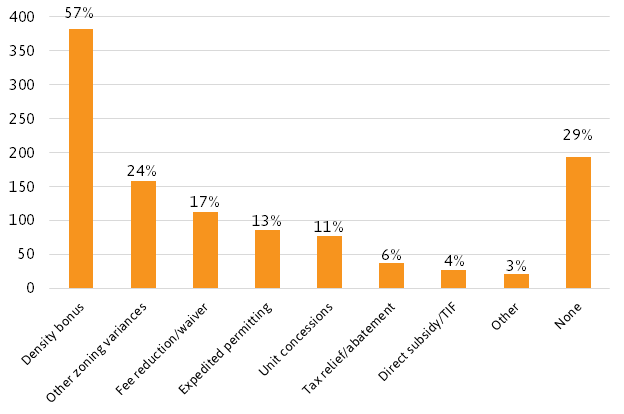

Most communities offer significant incentives to developers to offset the cost of providing affordable housing units. The most common incentive is the ability to build increased density. Another common incentive is to offer other zoning variances, such as reduction in site development standards, modification of architectural design requirements, and reduction in parking requirements. Other less commonly used incentives include waivers, reduction or deferral of development and administrative fees and/or financing fees, expedited processing, concessions on the size and cost of finishes of affordable units, tax relief abatement, and direct public subsidy. A 2021 study* also identified other incentives, such as issuing certificates of affordable housing credits, which are transferable and can be sold, and technical assistance from the city.

Program Distribution by Incentive

Source: Wang and Balachandran (2021)

These incentives are sometimes criticized as “giveaways” to developers. Calavita and Mallach* point out that incentives generally come at a real cost to the public sector. If inclusionary housing requirements are modest enough to be absorbed by land prices, then any incentives merely move the cost from landowners back onto the public. Incentives such as tax abatements and fee waivers reduce revenues available to jurisdictions just as cash subsidies to development projects would. Even planning incentives such as density bonuses, which appear free, result in increased infrastructure and other public costs.

When communities base inclusionary requirements on detailed feasibility studies, it becomes clear how incentives can play a role in maximizing the impact of an inclusionary housing program. If the goal of an inclusionary requirement is to enable developers to earn “normal” profits while capturing some share of “excess profits” for public benefit, any incentive a city can offer to make development more profitable enables the imposition of a higher inclusionary requirement than would otherwise be feasible. However, communities have to carefully weigh the costs and benefits of each incentive and evaluate them relative to the cost of meeting specific affordable housing requirements.

Density Bonus

The density bonus is the most common form of incentive used by inclusionary housing programs. Developers are allowed to build more housing units on a site if some of the units are set aside for affordable housing. Continue reading

Expedited Processing

Expedited processing moves projects with an affordable component to the front of the line in zoning, planning, and building permit processing. Continue reading

Fee Waivers

Many communities offer partial or full waivers of planning, permitting, or impact fees to projects that include affordable units. Continue reading

Parking Reduction

Some programs allow projects with affordable units to build fewer parking spaces than would otherwise be required under local zoning rules. Continue reading

Tax Abatement

Property taxes are one of the more significant annual expenses associated with housing. Some communities offer a partial abatement or complete waiver of property taxes to owners of projects with affordable housing. Continue reading

Common Questions

There are a variety of market responses to inclusionary housing policies. In some cases, developers must reduce their profits in the short term. Under some special circumstances—such as in highly desirable and fast-growing housing markets—housing prices may increase. In most cases, however, land values will drop in the long term and developer profits will return to normal.

In theory, an overly burdensome inclusionary housing program could push land prices so low that property owners choose not to sell and development slows. While there is no evidence of this occurring to a significant degree under a real program example, this risk may nonetheless exist. As a result, cities may want to avoid this outcome by offering developers incentives to offset their costs.

In addition, it is important to consider the fact that at any given level of economic impact for a particular inclusionary housing program, there is a choice. Your city can (1) have a lower affordable housing requirement with few or no incentives or (2) a higher requirement with offsetting incentives. The higher requirement may allow the program to produce more affordable units.

However, incentives don’t come without their own costs. The most useful and sought after one, a density bonus, can nullify the legitimacy of area plans with considerable public input for example. Reductions in open space or parking requirements can reduce make projects less acceptable to neighborhoods reducing support for the program

No: While higher density buildings can add value to a real estate project, these buildings cost more to build – sometimes much more. Even if the added income of having more on-site units is more than the cost to build higher, increasing the allowable density may not automatically add enough value to offset the cost of providing affordable housing. Many voluntary inclusionary housing programs rely on an increased density incentive to encourage developers to build affordable units. But the track record of these programs suggests that increased density alone is not enough of an incentive.

A Grounded Solutions Network (formerly Cornerstone Partnership) study of the voluntary incentive zoning program in Seattle, Washington, found that more than half of eligible projects forewent the bonus density and built only to the base height.* Opponents of the program claimed that this was evidence that the housing requirements were overly burdensome. However, a subsequent study concluded that many projects would not have built to the higher density even if it were available with no affordable housing requirement* mostly because of the dramatic increase in construction costs for steel frame high-rise buildings. While the bonus density was valuable, it was not valuable enough to offset the added construction cost in many cases. The result of Seattle’s voluntary program was that extremely profitable mid-rise projects were not required to contribute to affordable housing, while their less profitable high-rise neighbors were.

When considering whether to adopt or revise an inclusionary housing policy, local government agencies often retain an economic consultant to prepare a feasibility study. This study evaluates the economic tradeoffs of requiring a certain percentage of affordable units in new residential or mixed-use projects.

Feasibility studies help policymakers assure that new policies and programs are economically sound and will not deter development, while still delivering the types of new affordable units needed by the local community.

Feasibility studies are different than nexus studies, which are a similar type of analysis often used by local jurisdictions to establish residential or commercial linkage fees to fund housing programs. A feasibility study determines how a new inclusionary policy would affect market-rate housing development costs and profits. A nexus study quantifies the new demand for affordable housing that is generated by new commercial or market-rate housing development.

While every study differs based on the needs and market conditions of the specific area, in general they follow a similar outline:

- Introduction and Policy Context – A description of the purpose and scope of the study.

- Background Economic Trends and Market Conditions – An in-depth analysis of the local economy and the market conditions affecting residential development.

- Economic Analysis of Hypothetical Development Project – Based on prevailing economic conditions and using assumptions from the market analysis, an economic feasibility analysis uses development pro formas to test the economic impact of varying inclusionary requirement on hypothetical development projects or prototypes. This process of modeling how inclusionary requirements might affect the bottom line profitability of market rate residential development should include a sensitivity analysis. In the sensitivity analysis, assumptions from the market analysis loan interest rates, for example, are dialed to their highest and lowest reasonable levels to examine how sensitive the final estimates of profitability are to variations in cost and revenue assumptions.

- Findings and Recommendations – This section builds on findings from the financial feasibility analysis. It includes conclusions about the likely effect of requiring various percentages of affordable units at varying affordability levels in combination with certain types of developer incentives.

A few communities actively encourage developers to utilize other housing subsidies to help offset the cost of building required affordable units. This position seems to be more common in communities with a surplus of affordable housing funds. Many communities, however, face an acute need for affordable housing and high demand for scarce affordable housing subsidy funds. These cities will generally prohibit developers from ‘double counting’ units (i.e. using other affordable housing programs to subsidize units that are required by the inclusionary housing program) because these affordable housing funds are limited. To the extent that inclusionary developers are using public affordable housing funds to offset their costs, the program is not producing additional affordable housing beyond what would have been provided in any event.

Many cities adopt policies somewhere in the middle, allowing some affordable housing funds to be utilized but prohibiting others. In general, cities are more cautious about using funds that are highly limited. For example, many cities will allow developers to utilize tax abatements but prohibit the same projects from applying for housing grant funds. A second general guideline is that access to external funding should be balanced against the burdens required or requested of the developer. If cities wish to maintain their inclusionary policies, yet the inclusionary rules make development extremely difficult, they will often err on the side of allowing more external subsidies to be used.

Use of the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program can be more complicated in part because there are two different types of LIHTC. The so-called 9 percent credits provide a large share of the cost of eligible projects and as a result they are in very high demand and limited supply. The 4 percent credits provide relatively less subsidy and require relatively more investment from local sources and private debt, and as a result they are in less demand. An inclusionary project that accessed 9 percent credits might be ‘taking them away’ from another local affordable housing project while the same project could use the four percent credits without affecting other eligible local projects. For this reason there has been a trend for inclusionary housing programs to allow developers to use 4 percent but not 9 percent credits either in on-site or off-site projects.

San Francisco, California uses its tax credits to achieve deeper affordability. Generally, the city does not allow developments to use any subsidies (local, state or federal). However subsidies can be used, with written permission, to deepen the affordability of a unit beyond the level required by the program. Additionally, if 20 percent of their units are affordable to people making 50 percent of AMI, the four percent tax credit can be used. The percentage increases to 25 percent for off-site production.