Inclusionary housing policies have been adopted in more states and places than commonly thought. The most comprehensive nationwide investigation of inclusionary housing programs conducted to date identified 734 jurisdictions with inclusionary housing programs located in 31 states and the District of Columbia at the end of 2019 (Wang and Balachandran, 2021). In the study, inclusionary housing refers to “a set of local rules or a local government initiative that encourages or requires the creation of affordable housing units, or the payment of fees for affordable housing investments when new development occurs.” This definition includes impact or linkage fees that generate revenue for affordable housing.

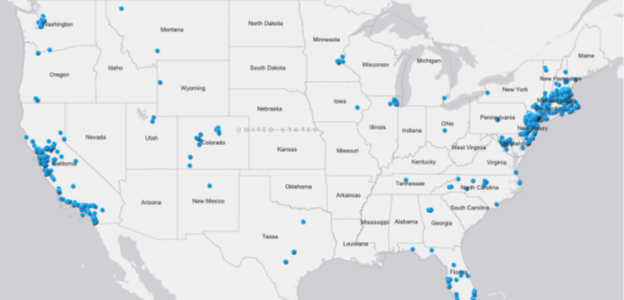

Location of Inclusionary Housing Programs in the United States

Source: Wang and Balachandran, 2021

The number of inclusionary housing programs in each state varies widely. A few states—primarily Massachusetts, New Jersey, and California—have highly-supportive state legislative frameworks. That has led to many more local inclusionary housing programs; nearly three-quarters of all programs in the country are found in those three states. However, supportive state legislation does not necessarily guarantee stronger or more productive programs. In fact, municipal programs in states other than Massachusetts, New Jersey, and California produce more affordable units (on average) than programs in those three states. Inclusionary housing has also established a critical mass in states such as New York, Washington, Florida, and Connecticut, where inclusionary housing policies can be found now in more than 20 localities.

Grounded Solutions Network’s interactive Inclusionary Housing Map includes updated data about local inclusionary housing programs nationwide as well as data on state-level legislation and judicial decisions that are related to the adoption of local inclusionary housing policies.

Common Questions

Probably not: Inclusionary housing relies on market growth to produce new affordable housing resources; it is not likely to be successful in communities that are not experiencing or anticipating growth. But inclusionary may not make sense for every growing community.

Smaller communities, in particular, sometimes lack the capacity to effectively administer inclusionary programs. Outsourcing and multi-jurisdiction collaborations could make smaller programs easier to administer by bringing together units from many local programs. But communities that produce very few units may find that the burden of administration outweighs the benefits of an inclusionary housing program.

Inclusionary housing may not be suitable in every type of housing market, but it can work in more places than many people realize. Inclusionary programs are tools for sharing the benefits of rising real estate values and, as a result, they are generally found in communities where prices are actually rising. In many parts of the United States, land prices are already very low, and rents and sales prices often would be too low to support affordable housing requirements even if the land were free. In these environments, policies that impose net costs on developers are unlikely to succeed (though some communities nonetheless require affordable housing in exchange for public subsidies).

The communities where rising housing prices are a real and growing problem are quite diverse and plenty, and are not high-growth central cities like Seattle. In California, one third of inclusionary programs are located in small towns or rural areas. Wiener and Bandy* studied these smaller-town inclusionary programs and found that many were motivated by the influx of commuters or second homebuyers entering previously isolated housing markets. They described what happened when developers began building high-end homes for commuters in Ripon, California. As Ripon very quickly became one of the San Joaquin Valley’s most expensive communities, local residents became increasingly concerned about housing costs. Ripon’s leaders set a goal that 10 percent of all new housing would be affordable. As Wiener and Bandy* describe:

The willingness of small jurisdictions, especially small cities, to overcome local politics and take bold and decisive action to adopt inclusionary housing programs is often a derivative of scale. People know their neighbors. They directly feel the shortage of affordable housing. They know where the few remaining parcels of developable land are located. They know that the character of their communities is changing. And, they have access to their elected officials who work in the same work places, shop in the same stores, and send their kids to the same schools.

While inclusionary policies are clearly relevant in a very wide range of communities, the appropriate requirements can be very different from one market to another. In communities where higher density development is not practical, higher affordable housing requirements may not always be feasible but lower requirements may nonetheless be effective. San Clemente, California requires only 4 percent of new units to be affordable, but produced more than 600 affordable homes between 1999 and 2006.* Wiener and Bandy* also found that many smaller jurisdictions relied heavily on in-lieu fees and some set fees at very modest levels.

Smaller communities with inclusionary housing programs must address unique considerations, such as limited staff capacity and costs of administration. Outsourcing and multi-jurisdiction collaborations can make smaller programs easier to implement, but there are some localities where the benefits of an inclusionary housing policy will not adequately offset its costs.