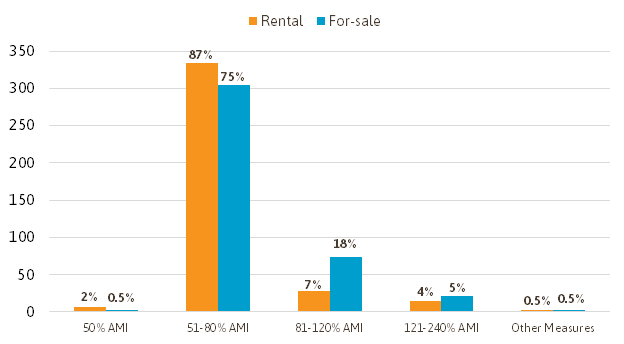

Cities require units created through inclusionary housing programs be sold or rented at “affordable” prices, but affordable to whom? Income targets and pricing are generally defined in terms of percentage of Area Median Income (AMI), and the majority of programs set the maximum income of eligible households between 51% and 80% of AMI.

Program Distribution of Maximum Income Level by Tenure and Affordability Level

Data source: Wang and Balachandran (2021)

In terms of development-level financial feasibility, there is a trade-off between getting more affordable units serving higher-income households or fewer affordable units serving lower-income households. The rental revenue from a unit serving 40% AMI households is half that of a unit serving 80% AMI households. Thus, serving 51-80% AMI households may be a rational way to maximize the number of units while also serving low-income households in need, many of whom are also over-income for federal programs. Most government-supported rental housing serves 30%-60% AMI households.

That said, most communities have the greatest housing shortage for households below 50% of AMI. In considering how to price inclusionary units, communities should consider doing a housing needs analysis of renters by income broken out by race; in many communities, renter households of color are disproportionately represented in lower income groups (below 50% of AMI).

We often get asked whether inclusionary housing can serve households below 50% of AMI. The answer is yes.

Serving Lower-Income Residents

Cities that want to create units for lower-income residents, including residents making below 50% of Area Median Income (AMI), have a number of options. Common strategies are to:

- Allow developers to provide fewer units with deeper affordability;

- Require managers of inclusionary units to accept Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers;

- Purchase the units and add additional subsidy to rent or sell them at alternative affordability levels; and

- Accept in-lieu fees and partner with nonprofits to build housing with deeper affordability.

Fewer Units with Deeper Affordability

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles’s Transit-Oriented Communities Incentive Program (a voluntary inclusionary housing program) provides three options for developers: make a relatively large percentage of units affordable at 80% of AMI, a modest percentage of units affordable at 60% of AMI, or a smaller percentage of units affordable at 30% of AMI. As of February 2020, half of the affordable units planned through the program are affordable at 30% of AMI.

Require Acceptance of Section 8 Vouchers

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Minneapolis’s Unified Housing Policy, which includes its inclusionary zoning provisions, requires owners of rental housing projects subject to the policy to accept tenant based rental housing assistance, including, but not limited to, Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers. This can be a win-win for the community and property owners, since owners can receive Fair Market Rent for units rented to voucher holders, and Fair Market Rent may be higher than the maximum rent permitted under the inclusionary housing policy.

Purchase the units and add subsidy

Montgomery County, Maryland

Montgomery County’s inclusionary ordinance grants a right to purchase one third of all inclusionary units to the local public housing authority, the Housing Opportunities Commission (HOC). Developers are required to offer the HOC and several other approved nonprofits a 21-day period to opt to purchase any new units before they are offered to homeowners. The HOC has purchased more than 1,500 units in 188 subdivisions (out of more than 10,000 inclusionary units produced in the county) using a range of housing programs including Section 8, Low Income Housing Tax Credits and State rental funds. In addition, 29 units have been purchased by other nonprofit agencies and rented to low-income residents. As a result of this partnership, Montgomery County has generally served a much higher share of low- and very low-income residents than typical in other inclusionary housing programs across the country.

Nonprofit Partnerships

In 2007, the Non-Profit Housing Association of Northern California conducted a study that looked at, among other things, the inclusionary programs in California that succeeded in providing housing for extremely low-income (ELI) households. They found that 68 percent, a disproportionately large number, of housing affordable to ELI households was produced through partnerships with nonprofit developers, most often through a joint venture where affordable units are built within or adjacent to the market-rate development. *

Common Questions

Cities often set affordability levels higher for ownership units than for rental units. For programs with a single income targeting requirement, 23 percent of programs set the maximum income at 81 percent of AMI or above for homeownership developments, compared to 11 percent of programs for rental developments. This pattern is consistent for programs targeting multiple income groups, which tend to have a higher percentage allocation in extremely low- and very low-income levels (50 percent of AMI or below) for rental units than for homeownership units. Data source: Wang and Balachandran (2021)

This policy is often dictated by market prices. For example, a household earning 80 percent of AMI may be able to afford the rental price for a median priced one-bedroom apartment, but cannot comfortably afford to buy a home. Pricing ownership units at 80 or even 120 percent of AMI meets this need. However, inclusionary rental apartments with their price set to be affordable for a household earning 100% of median income would often be the same price, or even more expensive, than regular apartments for rent in the area, so they aren’t necessarily serving a critical housing need

On the other hand, ownership units typically cost developers relatively more to produce. While it would be possible to require that developers price ownership units so that they serve the same income group that is being served in rental housing, this would have a greater impact on financial feasibility for ownership projects. Many cities have determined that allowing developers of ownership units to serve a higher-income group can reduce the burden of the program on ownership projects while still serving a real affordable-housing need.

It is not uncommon for cities to have a problem where their smaller units rent for close to market rate. This is largely the result of the unrealistic assumptions set forth in the federal income guidelines, which determine affordability levels. For example based on 2013 federal guidelines for Seattle, Washington, an affordable studio (at 80 percent AMI) could rent for up to $1,127, while a two-bedroom apartment could rent for $1,450. There is relatively little difference in price for very different apartments.

In response to this challenge, cities can adjust their rental formulas to require lower prices for smaller units. For example, if a two-bedroom unit is priced to be affordable to someone making 80 percent of AMI, a studio could be priced affordable to someone making 60 percent of AMI.

Inclusionary housing programs create affordable homeownership opportunities in three distinct ways:

- On-site homeownership units. When developers produce for-sale projects, most inclusionary housing programs require developers of ownership projects to provide affordable ownership units.

- Homebuyer assistance loan programs. Many cities directly operate purchase-assistance loan programs that make gap funding available to income-qualified homebuyers. These programs are sometimes called down-payment assistance, even though the levels of public subsidy often exceed what would be typical for a down payment.

- Nonprofit homeownership projects. Many inclusionary housing programs invest a portion of revenue from in-lieu fees or housing development impact fees in homeownership development projects sponsored by local nonprofit housing developers. These projects might be new construction of affordable homes or renovations of existing housing homes.

Some of the most compelling arguments for the need to ensure permanent affordability have come from analyses of federally-subsidized rental units (e.g. Project Based Rental Assistance).

According to an analysis by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), nearly half a million of the nation’s 1.4 million federally assisted rental units are at risk of leaving the affordable stock because of “owners opting out of the program, maturation of the assisted mortgages, or failure of the property under HUD’s standards.” NLIHC advocates for the need to preserve these existing units, pointing to research that indicates that it cost 40 percent less to preserve an existing affordable unit than to build a new one.

At the same time, if one goal of an inclusionary housing program is to create economic integration, we can only hope to maintain that economic diversity if we preserve the affordable housing units over a very long time. Inclusionary housing produces new housing relatively slowly, over time as communities grow. Inclusionary housing programs can build up sizable portfolios of homes in every part of the community, but if units are only maintained as affordable for relatively short periods of time, the most desirable locations are likely to remain out of reach for lower-income residents.

A few communities actively encourage developers to utilize other housing subsidies to help offset the cost of building required affordable units. This position seems to be more common in communities with a surplus of affordable housing funds. Many communities, however, face an acute need for affordable housing and high demand for scarce affordable housing subsidy funds. These cities will generally prohibit developers from ‘double counting’ units (i.e. using other affordable housing programs to subsidize units that are required by the inclusionary housing program) because these affordable housing funds are limited. To the extent that inclusionary developers are using public affordable housing funds to offset their costs, the program is not producing additional affordable housing beyond what would have been provided in any event.

Many cities adopt policies somewhere in the middle, allowing some affordable housing funds to be utilized but prohibiting others. In general, cities are more cautious about using funds that are highly limited. For example, many cities will allow developers to utilize tax abatements but prohibit the same projects from applying for housing grant funds. A second general guideline is that access to external funding should be balanced against the burdens required or requested of the developer. If cities wish to maintain their inclusionary policies, yet the inclusionary rules make development extremely difficult, they will often err on the side of allowing more external subsidies to be used.

Use of the Federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program can be more complicated in part because there are two different types of LIHTC. The so-called 9 percent credits provide a large share of the cost of eligible projects and as a result they are in very high demand and limited supply. The 4 percent credits provide relatively less subsidy and require relatively more investment from local sources and private debt, and as a result they are in less demand. An inclusionary project that accessed 9 percent credits might be ‘taking them away’ from another local affordable housing project while the same project could use the four percent credits without affecting other eligible local projects. For this reason there has been a trend for inclusionary housing programs to allow developers to use 4 percent but not 9 percent credits either in on-site or off-site projects.

San Francisco, California uses its tax credits to achieve deeper affordability. Generally, the city does not allow developments to use any subsidies (local, state or federal). However subsidies can be used, with written permission, to deepen the affordability of a unit beyond the level required by the program. Additionally, if 20 percent of their units are affordable to people making 50 percent of AMI, the four percent tax credit can be used. The percentage increases to 25 percent for off-site production.

While this is not common practice, several jurisdictions have programs that allow for or even encourage local housing authorities or nonprofits to purchase some inclusionary units.

For example, in Montgomery County, Maryland the public housing authority, called the Housing Opportunities Commission (HOC), has the option to purchase up to one third of all inclusionary units. The agency can offer approved nonprofits a 21-day period to opt to purchase any new units before they are offered to homeowners. The HOC has purchased more than 1,500 units in 188 subdivisions (out of more than 10,000 inclusionary units produced in the county) using a range of housing programs, including Section 8, Low Income Housing Tax Credits, and state rental funds. As a result of this partnership, Montgomery County has generally served a much higher share of low- and very low-income residents relative to other inclusionary housing programs across the country.