This report by the National Housing Conference’s Center for Housing Policy compares the range of affordability preservation mechanism used to protect public investment in affordable homeownership units. View Report

One of the primary benefits of shared equity homeownership over affordable rental housing is that shared equity homeownership offers the homeowner an opportunity to build wealth, while at the same time it provides the community with an affordable housing option for its residents. Programs strive to strike a balance between protecting affordability over time and encouraging asset building for the homeowner.

A resale formula can be used to help ensure this balance. While formulas vary from community to community, in all instances it is important to periodically review the performance of the formula to make sure it is indeed preserving affordability and achieving any wealth creation goals.

Well-designed inclusionary housing programs are able to offer home buyers meaningful and safe asset-building opportunities while also preserving a sustainable stock of homes that remains affordable for future generations.

A team from the Urban Institute studied economic outcomes for buyers in seven homeownership programs with long-term affordability restrictions. The study found that sellers were able to experience significant equity accumulation even when the resale prices were restricted to preserve affordability.* For example, the typical owner of an inclusionary unit in San Francisco, California, received $70,000 when he sold the home. Even with the strict price restrictions on resale, the typical owner earned an 11.3 percent annual return on the home investment—far more than would have been earned through other investment options.*

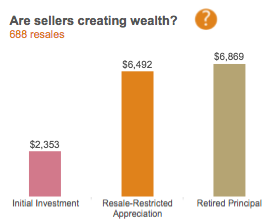

Grounded Solution’s HomeKeeper software is being used by over 60 programs to manage homeownership programs with long-term affordability controls. As part of the project Grounded Solutions tracks key social impact data from these programs and makes the results publicly available in an interactive Social Impact Dashboard.

Grounded Solution’s HomeKeeper software is being used by over 60 programs to manage homeownership programs with long-term affordability controls. As part of the project Grounded Solutions tracks key social impact data from these programs and makes the results publicly available in an interactive Social Impact Dashboard.

The HomeKeeper data shows just how effective these programs have been in balancing asset building and affordability. Even during the housing market collapse, shared equity homeownership programs were able to both maintain affordability and offer meaningful wealth-building opportunities.

The data as of July 2016 included more than 1000 resales from 34 programs spread across the country. It showed that the typical home was resold at a price that made it affordable to a lower income group than it had initially served and at the same time the typical seller earned a sizable return on their investment – more than they likely could have earned through any other widely available investment.

Some of the most compelling arguments for the need to ensure permanent affordability have come from analyses of federally-subsidized rental units (e.g. Project Based Rental Assistance).

According to an analysis by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), nearly half a million of the nation’s 1.4 million federally assisted rental units are at risk of leaving the affordable stock because of “owners opting out of the program, maturation of the assisted mortgages, or failure of the property under HUD’s standards.” NLIHC advocates for the need to preserve these existing units, pointing to research that indicates that it cost 40 percent less to preserve an existing affordable unit than to build a new one.

At the same time, if one goal of an inclusionary housing program is to create economic integration, we can only hope to maintain that economic diversity if we preserve the affordable housing units over a very long time. Inclusionary housing produces new housing relatively slowly, over time as communities grow. Inclusionary housing programs can build up sizable portfolios of homes in every part of the community, but if units are only maintained as affordable for relatively short periods of time, the most desirable locations are likely to remain out of reach for lower-income residents.

Nothing lasts forever, but many cities attempt to structure their inclusionary housing policies to preserve the affordable homes for as long as possible. Many argue that if inclusionary housing programs are to create and preserve mixed-income communities, long-term restrictions are necessary for the program to have a lasting impact. If homes expire out of the program after a few decades, the program can never really address the need for affordable housing.

Ownership programs typically record deed restrictions or covenants that limit sale or rental of a regulated unit only to approved low-income (or moderate-income) households. In some communities, these covenants are structured to run ‘in perpetuity.’ In others, they have a fixed term, generally somewhere between 30 and 99 years.

Affordability terms applied to rental developments are a bit more complex. An investor might pay more for a property with rent restrictions that expire after 15 years than one with 99-year restrictions, but the difference might be slight. In other words, the length of affordability makes a big difference to the long-term impact of the program and, at most, a small difference to initial feasibility.

The best practice is to record fixed, but long-term restrictions (50 or 99 years, for example) and re-record them and ‘reset the clock’ each time a property is sold or redeveloped. For example, if a property is sold 20 years after initial development, a new restriction is recorded with a new 50-year term. If the restrictions last approximately as long as the useful life of the buildings, there is a high likelihood that affordability will be maintained over time.

For homeownership units, the affordability restrictions can be reset each time a unit is resold. Rental properties may not sell as frequently, but eventually they will be torn down and rebuilt and the jurisdiction would be in a position to require new affordable units at that point.

Permanent affordability is frequently the goal for inclusionary housing programs, and a number of communities record affordability restrictions that are perpetual and ‘run with the land.’ However, legal concerns are often cited as reasons not to adopt perpetual restrictions. For several jurisdictions, this problem is solved by simply changing the term used. Davidson, North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Burlington, Vermont, San Mateo, California, and Redmond, Washington all chose to define their affordability term as “the life of the building” or 99 years, rather than “in perpetuity.”

Another way that programs get around concerns about “perpetual affordability” for single-family homes is to adopt control periods of 30 or more years and require that these terms restart for the next homebuyer if the home is resold within the control period. The administrators of programs in Montgomery County, MD, Fairfax County, VA and San Mateo believe, plausibly, that this reset requirement will have the same impact as “perpetual” affordability requirements, because most homes tend to be sold within 30 years.

Fairfax County uses its preemptive option to purchase homes at the first sale of the home after the control period expires. The preemptive purchase option is another way to protect inclusionary housing units and to extend their affordability in perpetuity; however, the jurisdiction must purchase the home at market price and then subsidize it to make it affordable, which can be very expensive and therefore reduces the impact of the original subsidy.

Another approach is to require repayment of a portion of sales proceeds in excess of the affordable price when a home reaches the end of the affordability period and is sold on the open market. Montgomery County and Fairfax County capture half of these proceeds if the home sells after the completion of the 30-year affordability term. Jurisdictions in New Jersey capture 100 percent of the difference between the affordable price and market price, but this is calculated as the difference that existed at the time of initial sale. In other words, these communities capture 100 percent of the original affordability subsidy.

Setting resale prices must balance the goal of preserving affordability and allowing homeowners to build equity. It is a good policy for cities to periodically reexamine their resale formulas. However, changing a resale formula has serious implications for the ability of the program to maintain long-term affordability and could impact marketing and financing and other elements of a program. Before changing the resale formula, cities should consider conducting an analysis that compares several alternative resale formulas side by side under several possible economic scenarios.

This report by the National Housing Conference’s Center for Housing Policy compares the range of affordability preservation mechanism used to protect public investment in affordable homeownership units. View Report

This report provides an easy to digest overview of the goals for shared equity resale formulas and describes some of the most common options. View Report

Grounded Solution Networks’ Video Learning Series offers an in-depth 60 minute course on developing an effective formula to preserve long term affordability for affordable homeownership units. View video